Wild Hijiki Seaweed

Hijiki is often described as an edible seaweed that looks like brown twigs or black tea leaves, smells bracingly like a forest after a rain shower, has the chewy texture and subtle earthy flavor of grains, and is rich with minerals and umami like mushrooms (and also performs in cooking like mushrooms in that it readily soaks up and carries the flavors of other ingredients). While analogies can be helpful in getting to know and appreciate a food and gain perspective on how to cook it, it’s always best to find the words to try to describe a food uniquely for what it is, especially when learning how to understand the foods of the sea and expand one’s use of them.

Hijiki is a sea vegetable. In fact, it’s an extraordinary sea vegetable that’s not comparable to any land or other sea vegetable. High in fiber, it has a unique salty sea, slightly sweet, rich taste and what in Japanese is called a “mochi-mochi,” or plump, chewy texture. It’s brownish-green when fresh, but turns nearly black when dried. It’s probably the easiest seaweed for anyone to like. It’s also one of the best to eat. In the Setouchi, hijiki is a primary source of supplemental iron as well as an important source of calcium, iodine, magnesium, and potassium. Another health benefit—it has virtually no calories. It’s so flavorful and nutritious that it’s consumed almost daily in the region in some type of dish or another, including onigiri rice balls, salads, and all kinds of simmered dishes. It’s even added to sweets. For thousands of years, it has been a staple food item in the Setouchi pantry based on preserved remnants found in ancient jars on Shikoku Island.

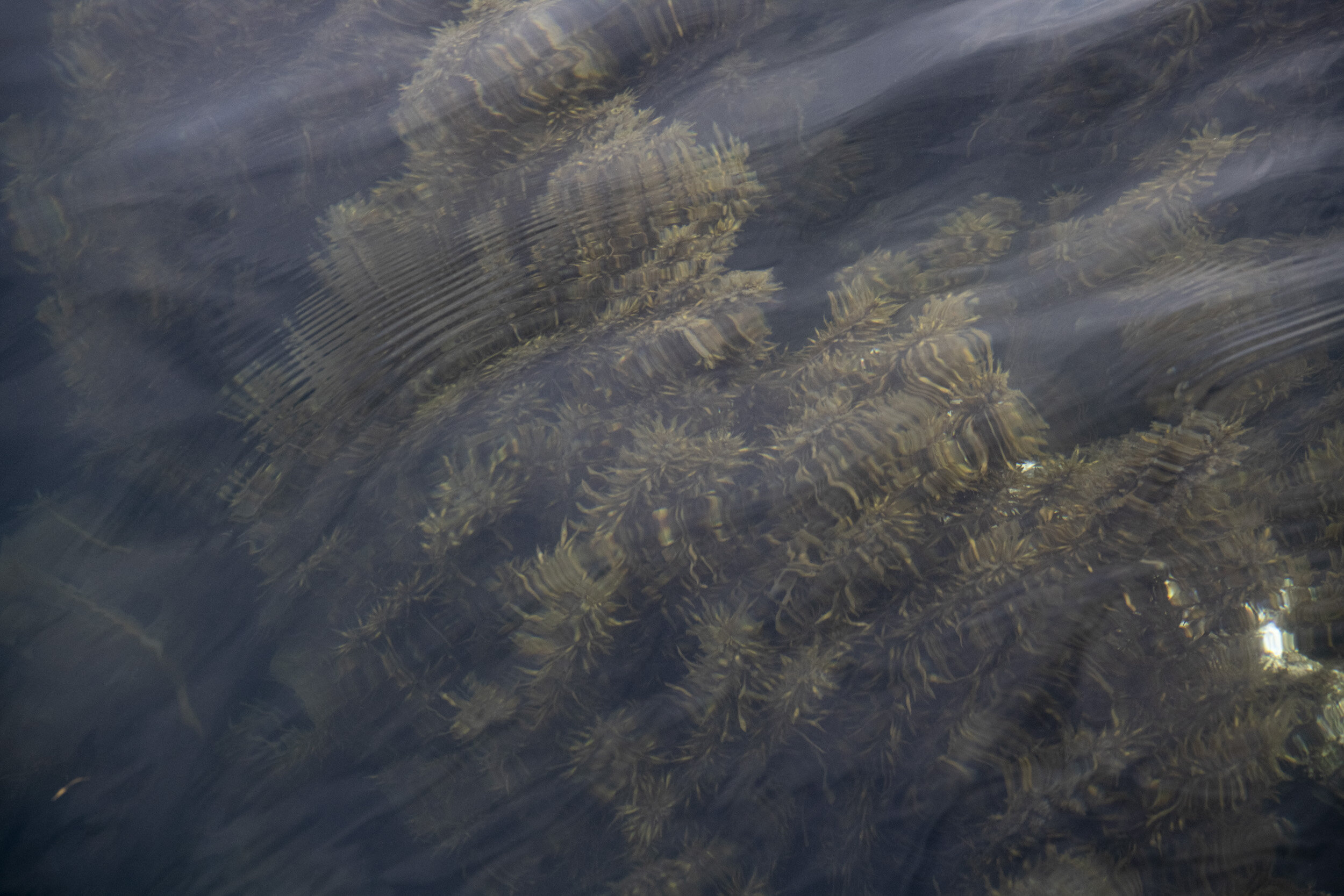

Hijiki grows wild on rocky outcroppings along the coast of southern Japan. It especially thrives in the calm waters of the Seto Inland Sea, growing abundantly on the extensive shoreline of the Setouchi’s many islands. It’s a spring vegetable, which is typically foraged for a few brief days in April by local fishermen, as a fisherman’s license is required to harvest it in the Setouchi. The conditions can be challenging. The fishermen often have to enter the cold water in the middle of the night if that is when the tide is at its lowest. They then cut the hijiki with small sickles, leaving several inches at the base so that the plant can produce a new crop the following year.

Once collected, hijiki needs to be processed quickly because its quality deteriorates when it is wet in the open air. The fishermen either wash the hijiki in fresh water, lay it out on racks to dry by the sun, and then bring it to small central processing facilities on the islands where it is steamed and once again dried. Or they process it themselves by hand by even more traditional methods. These include boiling the hijiki for two to three hours in large iron pots that are believed to enhance hijiki’s flavor as well as boost its iron content.

During the final drying process the leaves naturally fall away from the stems. The leaves, called me-hijiki, have a soft, fluffy texture and are the mildest in flavor. The long, sinuous stems, called naga-hijiki, have a stronger sea flavor and are chewier. One of the oldest forms in the Setouchi of the ancient practice of drying foods to preserve and concentrate their flavor, dried hijiki will keep for years.

How To Use

The best dried, wild hijiki has a nearly black color and no sign of white oxidation. The finer the leaves and stems the better. They’re sweeter and more tender. Before it can be used, hijiki needs to be rehydrated in water. Put it in a large bowl of cold water and let it soak for 15-20 minutes for me-hijiki and 25-30 minutes for naga-hijiki. It’s ready when soft. Put it in a colander, rinse under cold water, and drain. Soaked, its volume expands by ten times, so be sure to choose a large enough bowl.

Once rehydrated, hijiki can be used “as is” added to salads and other cold dishes. It’s at its best when it’s been heated with seasonings, which takes advantage of its ability to absorb other flavors. It goes well with other rich, dense foods that also absorb flavors and benefit from a bit of simmering in a sauce. It can then be served warm after the flavors have had a chance to meld or cold after being refrigerated because the juiciness of hijiki ensures a good flavor when chilled. Any dish—soups, stews, or simmered dishes—that needs some added umami-richness, interesting color and texture, and dose of vitamins and minerals will be improved by hijiki. Hijiki’s mild “oceany” taste and satisfying chewy texture make it a great way to create a vegetarian or vegan, “seafood” type of dish without using fish.

Hijiki is also an excellent ingredient in making fiber- and mineral-filled furikake, a traditional mixture of dry foods and seasonings that is used to season dishes and as a condiment on foods. Yutaka Foods, the central processing facility for much of the foraged hijiki in the Tobishima Kaido Island chain, makes several delicious hijiki furikake, including Shiso-Hijiki, Ume Plum-Hijiki, and Chirimen-Hijiki, which is a mix of dried tiny whitefish, hijiki, sesame seeds, and other flavorings.

Where To Buy

Foraged, wild hijiki is widely available across the Setouchi because foraging it is an important source of supplemental income for the region’s fishermen. Look for it at roadside farmers markets called Michi no Eki and Umi no Eki and also at souvenir shops, gift stands at seafood restaurants, and the ports where the fishermen work and sell their freshly-caught fish and homemade seafood products. In Tokyo it’s also available at the “antenna shops” of some of the prefectures of the Setouchi, which feature regional craft foods. It’s a very light-weight and rewarding food to pack in your suitcase and take home with you.